The 807th anniversary of the issuing of the Magna Carta passed last week on June 19th, 2022. While many have argued for centuries that the signing of this document was the beginning of individual and parliamentary freedoms that we see today, it however also has an important role in the shaping of the natural history of the English countryside. Actually, King John didn’t “sign on the dotted line” as it has been shown in books to school children in the past, like the beautifully illustrated children’s book by LadyBird shown here. King John’s Privy Counsellor provided a wax seal with the King’s insignia to stamp and authenticate each copy of the document.

Lost in all the intellectual legal debates surrounding the Magna Carta are two very important components of the charter that had an enormous impact on the future English countryside. These were clauses that dealt with forestry and fishing rights of freemen and nobles.

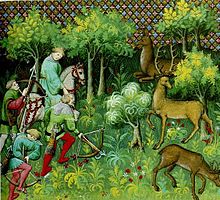

In an earlier post I outlined how much could be derived from the Doomsday Book about the natural history of England in the middle of the 11th century. The Doomsday Book was essentially an inventory of what land and physical assets were available to the new English monarch. William and his descendants put the Doomsday Book to good use by beginning to establish “Royal Forests” for exclusive use of the monarch and his family on the best available land. “Royal Forests” were not just wooded areas, but more an enclosed “common” area including meadows, streams, wetlands and even villages. In the enclosed area the King (and his servants) had exclusive access to chase and hunt animals. No one else was allowed to utilize the land and doing so, would probably mean death for the poor person caught trespassing. Under the Norman Kings “Royal Forests” continue to encroach upon the land of both nobles and freemen. It is estimated at the time of King John, an estimated third of England was under “Royal Forest”! Making an intolerable situation as freemen and nobles both utilized these areas for game hunting, fuel for fire and small-scale farming. At the time of King John the “Royal Forests” had become an enormous source of revenue for the crown as it allowed them to feed both their households and armies. The King also “gifted” hunting privileges to many of his favorites, making for truly a class system on who could use the land.

It is no wonder that the nobles insisted on forestry clauses being in the Magna Carta (clauses 44, 47–48 and 53)! The insistence was so strong that the noblemen re-issued the forestry components in the Charter of the Forest in 2017. This charter was sealed by King Henry III, John’s heir. This powerful charter established the patter of “common usage” of the forested areas, specifically allowing commoners to cut wood, forage for food and graze farm animals. Hunting of deer and other animals was still strictly controlled by the nobles.

What does all this mean to the natural history of England? Approximately from the time of the William’s conquest to the reign of King John, close to one third of England’s landscape was inaccessible to no one other than the crown and their favorites. England’s landscape during those two centuries must have become heavily forested by the time of the Magna Carta. As most foresters will tell you, forests will regenerate quickly with the removal of people and agriculture. What this meant for animals that were hunted in the Royal Forests is uncertain, although it is fair to assume from contemporary accounts that Norman kings harvested the forests liberally without much thought to sustainability or conservation.

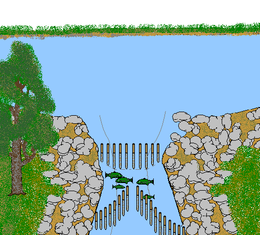

The second piece of the puzzle of the Magna Carta and the natural history of England has to do with fishing. While the Norman Kings had an impact on expanding woodlands on the English landscape, they probably had the exact opposite effect on fisheries. Many are unaware that at the time of the Norman conquest, the Thames and many other inland river systems used to “teem” with Atlantic Salmon . So much so, that after the Norman conquest it became common for Kings to establish large scale fishing weirs on many of England’s inner river systems, including of course the Thames.

Again, the Norman Kings derived much of their revenue from this practice and fed their households, armies and granted favors to their friends. Fishing weirs were very effective in wholesale capture of fish and eels. However they also had the effect of removing fish for anyone else, not to mention making the river systems impassable for transport. As a result, the English nobles insisted on the following clause in the Magna Carta: “All fish-weirs shall be removed from the Thames, the Medway, and throughout the whole of England, except on the sea coast”. The aftermath appears to have been positive, as Atlantic Salmon began to make a re-appearance in England’s inner River systems after 1215. Of course, Atlantic Salmon would later disappear in English rivers to other human causes later in history but that’s another blog post!

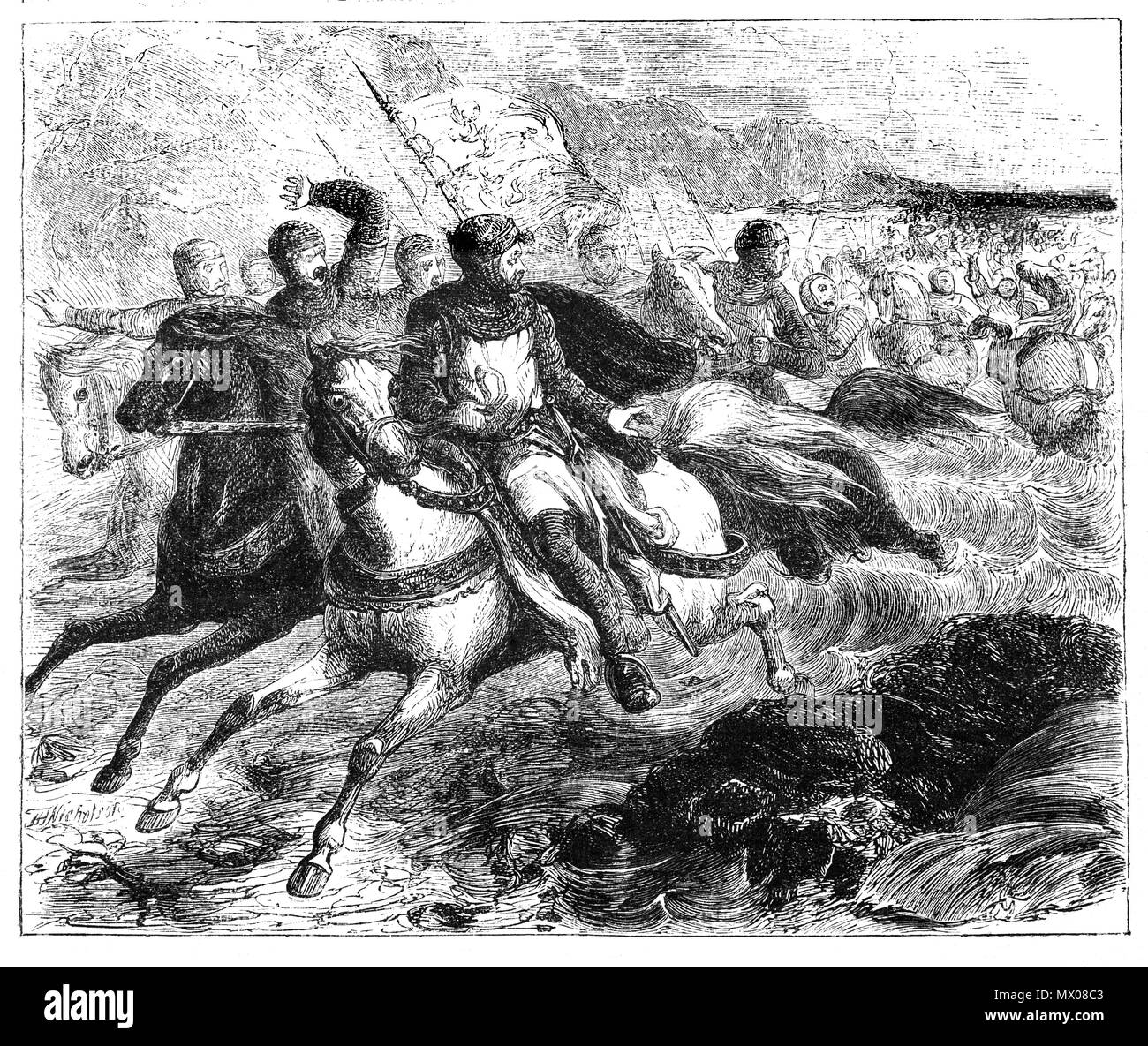

Another natural history “aside” about King John is regarding the story of how he “lost his crown jewels”. Many school children have been told the tale of how King John lost his crown jewels in England’s eastern large estuary the “Wash”. The story appears to be both a little bit of fact and a little bit of myth.

Apparently in 1216 John was on a military campaign in the far east of England near the Wash. It is unclear what exactly happened, but while marching to the town of King’s Lynn he appeared to have lost part of his baggage train containing his crown jewels in the strong tidal pools. Some contemporary historians have doubted the story, pointing out that King’s Lynn is in fact approximately 10km from the actual Wash. What they fail to realize is that the Wash at that time was much wider than it is today. So much so that King’s Lynn was a very active port city in this time period. Similar in many ways to Bruges, Belgium during this time frame. Contemporary accounts also document a very treacherous coastline on the Wash with fast moving tidepools that could immediately drown people and horses! England at this time was nearing the end of the great Medieval Warming Period that saw higher coastlines throughout much of the world.

King John died shortly after this incident and one of his successors, Henry III was apparently crowned with the original crown jewels of Edward the Confessor the last Anglo-Saxon king in 1220. The crown jewels this “lost baggage” actually contained is uncertain. However, it has provided much fodder for treasure hunters over the many years! It also of course provides certain clues to the shape and structure of England’s former coastline.

Of course King John being “King John” reneged on the Magna Carta plunging England into decades of turmoil after his death. However this document and accompanying stories about him provide us with excellent clues as to what the natural history of England was like during the 13th century!

Thank you for reading our Blog Post! This review was written with the assistance of “Grammarly”. Grammarly is an amazing FREE tool that allows anyone to write like a professional! For more information and a free download, click here.

For our Reviews of excellent books on Natural History, Archaeology and Technology, please visit our main website!