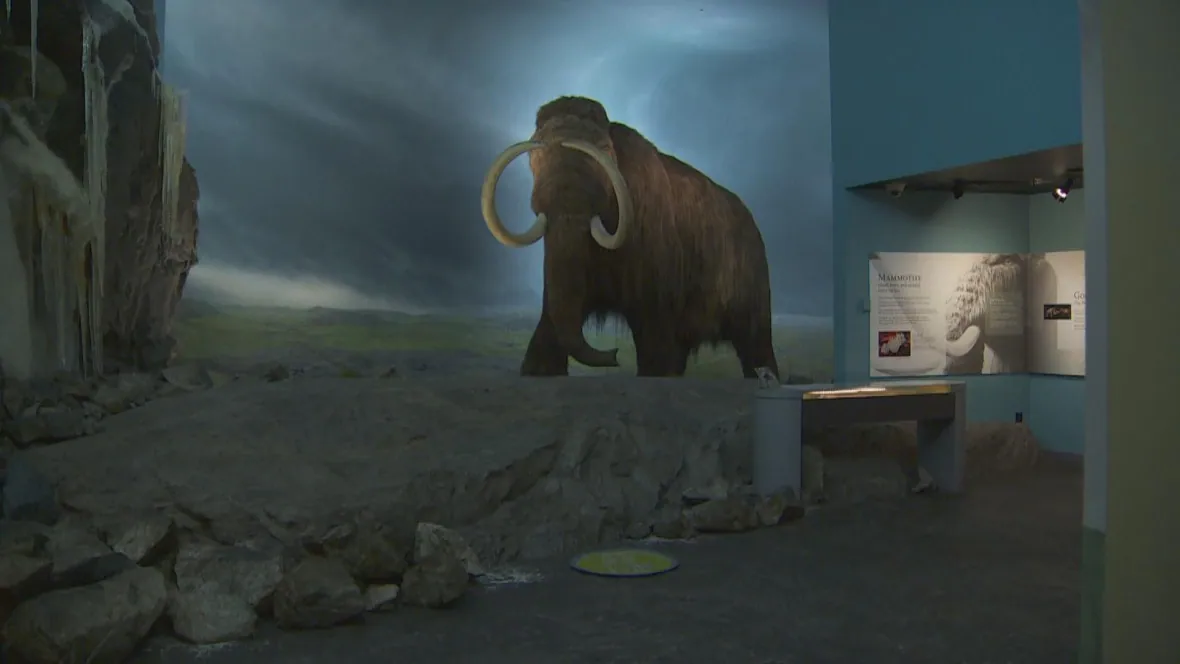

The announcement last week that the Canadian British Columbian government would cancel its proposed $789 million (Cdn) renovation of the Royal BC Museum came as no surprise. The project which would see a complete rebuild of the museum on a different site with the current structure remaining closed for 8 years. The rebuild was widely criticized and consider a “vanity project” by many. Premier John Horgan stated he heard British Columbians “loud and clear” and that it was the “wrong project at the wrong time”. A poll conducted by the Angus Reid Institute said that a full 69% of BC residents opposed the museum renovation plan. More revealing were the many comments from the public on news sites that were outraged at the project. Fortunately, the cancellation did not include the ongoing construction of the Museum’s new $224 million (Cdn) collections center in nearby suburban Colwood. The museum administration has announced that it will continue to engage with the public on what its future direction should be.

The announcement last week that the Canadian British Columbian government would cancel its proposed $789 million (Cdn) renovation of the Royal BC Museum came as no surprise. The project which would see a complete rebuild of the museum on a different site with the current structure remaining closed for 8 years. The rebuild was widely criticized and consider a “vanity project” by many. Premier John Horgan stated he heard British Columbians “loud and clear” and that it was the “wrong project at the wrong time”. A poll conducted by the Angus Reid Institute said that a full 69% of BC residents opposed the museum renovation plan. More revealing were the many comments from the public on news sites that were outraged at the project. Fortunately, the cancellation did not include the ongoing construction of the Museum’s new $224 million (Cdn) collections center in nearby suburban Colwood. The museum administration has announced that it will continue to engage with the public on what its future direction should be.

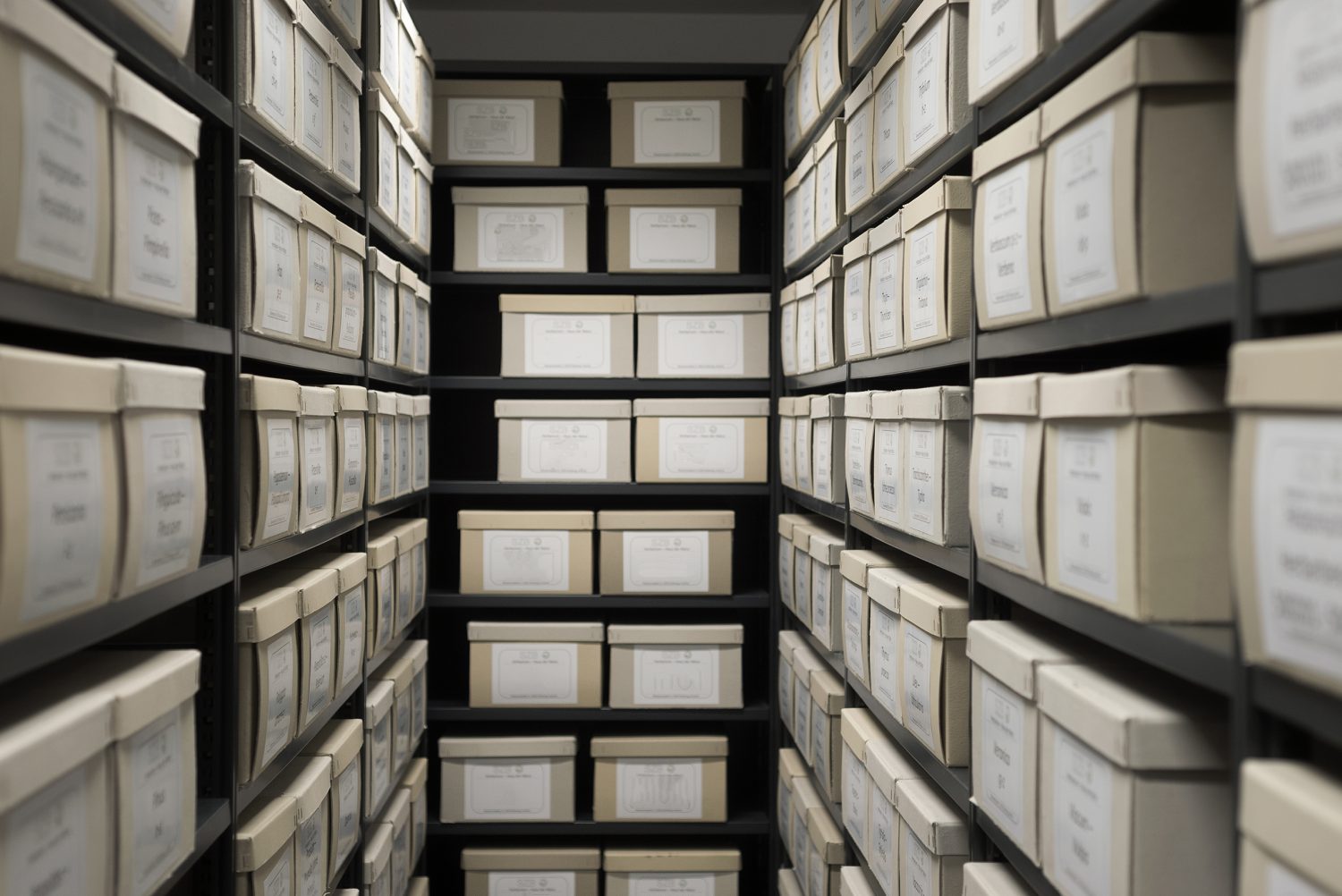

What does this mean for the future of museums generally? Does this cancellation have dire warnings for the museum industry? Unfortunately, many of the larger museums (and other institutions like libraries and archives) in urban centers are facing similar circumstances in the future. Many structures housing museums, libraries and archives in the “anglo-domain” were built in the midst of the baby boom era. Many structures were built in the 50s, 60s and 70s which are well over due to be replaced. Many of the buildings contain asbestos for insulation as well as outdated plumbing and wiring. With government funds lacking and the public appetite for new buildings waning, what does the museum industry do to move ahead?

One answer seems to be the “smaller regional model”. In British Columbia’s case, some of the loudest critics of the project were the smaller regional museums who are notoriously short of funding for their own facilities and collections. Several First Nations proposed they would like their artifacts back in their communities in their own museums.

Canada and many other nations in the “anglo-sphere” have all adopted the model of large urbanized centralized museums with much smaller and poorly funded regional cousins. While I’m a big believer in the smaller regional model, it is not without its difficulties. Smaller museums usually have deplorable facilities which would require considerable construction expense to enhance. Also, there are questions as to whether smaller regional museums would be able to bring the scientific and collection management expertise required to administer artifacts. This model still requires the recruitment and training of professional curatorial staff, something very hard to do in smaller centers. Also, there is the small “p” political questions, which regional communities and museums would get funding? What would be the criteria for granting this funding? Which communities would win in the funding criteria and who would lose?

The smaller regional model however, would provide many tourism and related economic benefits to communities that have received very little funding over the past 50 years. It would also bring newness and energy to these communities not seen for many years!

Let’s face it, regardless if the adopted model is large urban or regional, museums done properly are expensive! They require proper construction to protect the artifacts and professional curatorial staff to document and administer the collections.

What does this mean for the museum industry’s future? Future survival will require museums to make a much better business case for why they exist. The business case needs to outline both economic and scientific impacts with a strategy on making these widely known to both the government and public. In a former blog post, I pointed out that “Economic Impact Statements” should be at the ready of museum administrators. This is something that is sorely lacking on the Royal BC Museum website. No where could I find any Economic or Scientific impact statements. In a world with lots of noise, you are required to “toot your own horn” loudly!

Lofty statements of increased “tourism” dollars probably are not going to cut it in the future for any public museum. Real projects need real numbers with an accessible Business Case for both the public and governing authorities!

Thank you for reading our Blog Post! This review was written with the assistance of “Grammarly”. Grammarly is an amazing FREE tool that allows anyone to write like a professional! For more information and a free download, click here.

For our Reviews of excellent books on Natural History, Archaeology and Technology, please visit our main website!

In a previous

In a previous  Technology is making this type data gathering much easier. Gone are the days when it took considerable staff time to ask visitors for demographic information. One of the methods to gather information that I would recommend is the use of QR codes. It is now easy to display a QR Code in your museum on a sign that says “Please Help us Out by Answering a Few Questions”. Your guest can then use their smart phone to scan the QR code and quickly answer your demographic survey. Hint: please make certain your survey is really just a few questions! Notoriously long surveys are often abandoned by participants. You will find that if the survey is short and concise, visitors will be more than willing to provide their demographic information. There are several relatively inexpensive online services that can help you with this and Google is much better at helping you to locate them than I am.

Technology is making this type data gathering much easier. Gone are the days when it took considerable staff time to ask visitors for demographic information. One of the methods to gather information that I would recommend is the use of QR codes. It is now easy to display a QR Code in your museum on a sign that says “Please Help us Out by Answering a Few Questions”. Your guest can then use their smart phone to scan the QR code and quickly answer your demographic survey. Hint: please make certain your survey is really just a few questions! Notoriously long surveys are often abandoned by participants. You will find that if the survey is short and concise, visitors will be more than willing to provide their demographic information. There are several relatively inexpensive online services that can help you with this and Google is much better at helping you to locate them than I am. I’m in awe and envious of the British Natural History Museum’s new

I’m in awe and envious of the British Natural History Museum’s new

Natural History museums across the world for the most part are missing out on a tremendous opportunity for their guests and members. It may be bit of a surprise to many Natural History museum patrons that their museum usually also has a library. It is usually reserved for museum staff and is oftentimes stuffed away in some dark and dank room in a basement. If a museum is large enough it may even have a staff librarian or a clerk to maintain it. Why not bring this library material out into the open and make it available for museum guests and members to browse or borrow? Why not make it a display and a part of the exhibits? What better way to increase the knowledge of visitors than to give them access to books and journals on the very topics your museum is advocating for? It would also be an additional service that you could offer your members with their annual fees.

Natural History museums across the world for the most part are missing out on a tremendous opportunity for their guests and members. It may be bit of a surprise to many Natural History museum patrons that their museum usually also has a library. It is usually reserved for museum staff and is oftentimes stuffed away in some dark and dank room in a basement. If a museum is large enough it may even have a staff librarian or a clerk to maintain it. Why not bring this library material out into the open and make it available for museum guests and members to browse or borrow? Why not make it a display and a part of the exhibits? What better way to increase the knowledge of visitors than to give them access to books and journals on the very topics your museum is advocating for? It would also be an additional service that you could offer your members with their annual fees. Yes, I understand the complexities of running even a small library and the fact that you will want certain parts of the collection reserved only for staff. Of course, you would also need to take additional care and precautions surrounding any Archival material. However there has never been a more perfect time to offer this service. Open-source library software has made automation much cheaper. (

Yes, I understand the complexities of running even a small library and the fact that you will want certain parts of the collection reserved only for staff. Of course, you would also need to take additional care and precautions surrounding any Archival material. However there has never been a more perfect time to offer this service. Open-source library software has made automation much cheaper. ( A national natural history museum that I plan to re-visit and review this fall is the Canadian Museum of Nature located on Ottawa, Ontario, Canada,

A national natural history museum that I plan to re-visit and review this fall is the Canadian Museum of Nature located on Ottawa, Ontario, Canada,  When one thinks of Natural History Books, the topic of “Porcupines” often does not come to mind. This ubiquitous creature often does not make it to the top of the list when it comes to writing nature books. Indeed, there has not been much published about this amazing animal. The Library of Congress only has 220 books under the subject “porcupine” and the British Library only lists 28! The vast majority of the books listed are children’s fiction books, usually with a heartwarming tale how a prickly porcupine learns to fit in with other animals that don’t at first accept them. A perfect example of this is “How Do You Hug a Porcupine?” by Laurie Isop, with the book summary: “Can you imagine hugging a porcupine? Sure, it’s easy to picture hugging a bunny or even a billy goat, but where would you begin to try to hug a porcupine? After seeing all his friends hug their favorite animals, one brave boy works up the courage to hug a porcupine, but the porcupine isn’t so sure he wants to be hugged!”

When one thinks of Natural History Books, the topic of “Porcupines” often does not come to mind. This ubiquitous creature often does not make it to the top of the list when it comes to writing nature books. Indeed, there has not been much published about this amazing animal. The Library of Congress only has 220 books under the subject “porcupine” and the British Library only lists 28! The vast majority of the books listed are children’s fiction books, usually with a heartwarming tale how a prickly porcupine learns to fit in with other animals that don’t at first accept them. A perfect example of this is “How Do You Hug a Porcupine?” by Laurie Isop, with the book summary: “Can you imagine hugging a porcupine? Sure, it’s easy to picture hugging a bunny or even a billy goat, but where would you begin to try to hug a porcupine? After seeing all his friends hug their favorite animals, one brave boy works up the courage to hug a porcupine, but the porcupine isn’t so sure he wants to be hugged!”